This post is going to build toward

talking about the UA game, but it's also going to be my first general

introduction to some important concepts in defensive football. We're

going to look at some defensive structures before getting into the

problems that UA caused for them.

I wrote the bulk of this post before the CU game, so some new issues obviously came up. I won't comment on much of that here, so this post is really just an isolated commentary on our UA gameplan. I'll also say that I couldn't bring myself to break down last year's defense, and I've since deleted all digital memory of that horrible season, so I can't immediately compare it to Buh's defense except on a general level. Theoretically it'd be awesome and really informative, but for me the ratio of frustration to value wouldn't be worth it when we have the current season to talk about.

I wrote the bulk of this post before the CU game, so some new issues obviously came up. I won't comment on much of that here, so this post is really just an isolated commentary on our UA gameplan. I'll also say that I couldn't bring myself to break down last year's defense, and I've since deleted all digital memory of that horrible season, so I can't immediately compare it to Buh's defense except on a general level. Theoretically it'd be awesome and really informative, but for me the ratio of frustration to value wouldn't be worth it when we have the current season to talk about.

Defensive Concepts

I've already talked a little bit about coverage shells and the most

general characteristics of each coverage, so this post will talk more

about fronts and techniques in an effort to fingerprint our defense.

To get started talking about defensive fronts, let's recall the way

that gaps and DL assignments are called.

Run defense operates on the understanding that, because a

ball-carrier can't run through another human being, as long as the

defense can cover all of the spaces, or “gaps,” between offensive

blockers, they should be able to shut down the run. Therefore, the

defense won't be worried about individual blockers per

se,

but rather about open spaces on either side of those blockers. These gaps are labelled with a letter

starting from the inside out. The gaps outside the center are the

A-gaps, the gaps outside the OG's are the B-gaps, the gaps off-tackle

are the C-gaps, and anything outside a TE (or far outside an OT when

there is no TE) are the D-gaps. So, when you teach your defense what

their assignments are, you'll tell the NT that he's responsible for

the A-gap, the DT that he's responsible for the B-gap, etc., and

you'll make sure that you've assigned each gap to someone. So how many gaps are there? If X = the number of blockers, then the number of gaps = X + 1. A spread formation with just the five OL as blockers will be best defended with six front defenders, an I-formation with 5 OL + 1 TE + 1 FB will be best defended with eight front defenders, etc.

This is different from the way that you'll call alignments.

Alignments are labelled by number, and tell a defensive player where

to line up relative to an offensive blocker:

Even numbers indicate that the defender should line up heads-up over

the offensive blocker. Odd numbers indicate that he should line up

shaded outside of the blocker, and even numbers with an “i” added

mean that he should line up shaded inside the blocker. These numbers

increase as you work from the inside out. So, a 0-technique lines up

heads-up over the center. A 2-technique lines up heads-up over the

OG. A 3-technique lines up in an outside shade on an OG, and a

2i-technique lines up shaded inside an OG. The TE numbering is weird

and I'm not sure anyone knows why, but for whatever reason an inside

shade on a TE is called a 7-technique, while an outside shade on the

TE is a 9-tech.

The combination of a player's alignment (technique) and assignment

(gap) tells you how the play is going to work. So, a typical

alignment and assignment might tell your DT to line up in a

3-technique and to play the B-gap:

Whatever he does, he can't let the RG get outside of him (or the RT get inside of him). It's OK if

he gets blocked a little so long as he can stay in between the RG and RT, because as

long as he's doing that he's got the B-gap covered.

You can also use this system to indicate line movement. I could have

that DT line up in a 3-technique, but then angle inside to the A-gap:

No matter what the defensive call is, every player in the front will

be given their alignment and assignment according to this system.

The assignments for individual players will look something like that.

From that nomenclature we can start building up into different

defensive structures. The two most common defensive fronts in the

4-3 are the “shifted” fronts referred to as “over” and

“under.” These fronts are said to be “shifted” because they

put a DL over the C, and only one of the offensive guards.

Whichever side has the OG covered, we can say that the defensive line

is “shifted” in that direction. This “shifted” side of the

formation is most commonly called the “reduction.” The

characteristic feature of an “Over” front, then, is that the

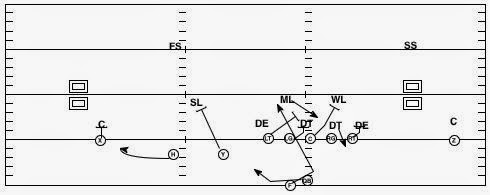

reduction is set to the TE:

This front is shifted toward the diagram's right, where we're

covering the C and the RG, and away from the diagram's left,

where the LG is uncovered. In terms of our nomenclature, in a

typical over front, on the TE side of the diagram the DT is a 3-tech

and has the B-gap. The DE is a 7-tech and has the C-gap. Away from

the TE, the NT plays a 1-tech and has the A-gap while the DE plays a

5-tech and has the C-gap. To simplify things for talking about the

LB's, we can say that the SLB has the D-gap outside the TE, the MLB

has the A-gap to the TE side, and the WLB has the B-gap away from the

TE, although as we'll see LB assignments are more complicated than

this.

This is contrasted with the “under” front, which shifts the DL

away from the TE:

The under front puts the reduction away from the TE. So, from left

to right, the DE is a 5-tech C-gap player, the DT is a 3-tech B-gap

player, the NT is a 1-tech A-gap player, and the DE is a 5-tech C-gap

player. Because this front is shifted away from the TE, it'll also

put the SLB on the LOS as a 9-tech D-gap player to get an extra guy

on the LOS. The MLB has the B-gap to the TE, and the WLB has the

A-gap away from the TE.

Why does it matter where you put the reduction? Don't you have all

the gaps covered regardless? Basically, it all comes down to who's

controlling which gap. It's hard to run through a gap that a DL is

covering, and for some blocking schemes it's impossible. The DL are

275-300 lb. guys doing their best not to move, and for the most part

they're responsible for one gap and only one gap. On run plays

they're stuffing that one gap, and on pass plays they're pass-rushing

through that one gap. There aren't a lot of blocking schemes that

can get them out of there. Accordingly offenses want to attack the

“soft” gaps that are covered by LB's. LB's are starting out off

of the LOS, they have to worry about reading run or pass, and they

have to flow with the ball on lateral plays. Basically, there's a

lot going on for the LB's that keeps them from racing straight

downhill into their gap, making it easier to block them out of their

assignment. When a DC is choosing where to place the reduction he'll

have this in mind. Say that an offense's best running play is to the

TE-side B-gap. Well, the DC might call an over front, which will put

a DT in that gap and make it hard to run that play. This is just one

out of many considerations, as we'll see below.

Art Kaufman's

Defense: Front Play

It looks to me like our base defensive call is Under Cover-4

(although we do mix in a fair amount of Over, and in coverage we play

Cover-0 and Cover-1 with varying degrees of frequency according to situation and gameplan). If any of you read my BI post on

Buh's defense long, long ago, this might terrify you, because it's

the same base defense. The devil is always in the details, though.

There are only a limited number of defenses that most college teams

base out of (generally either the over, under, or odd (classic 3-4)

front combined with Cover-1, Cover-2 (or 2-man), Cover-3, or Cover-4

behind it), but there are tons of ways to play each of these fronts

and coverages. So, calling our defense a 4-3 gives you almost no

information. Calling our defense an Under Cover-4 is a little

better, but still won't distinguish it from many of the other defenses

out there. For the rest of this post, we'll look at some little

details that make our defense what it is.

In the previous section I talked about placing the reduction either

to or away from the TE side of the formation. We've played against a

lot of spread formations that use no TE, so our front obiously can't

be set based on where a TE lines up. We usually run an under front,

meaning that we'll put the reduction away from the “strong side”

of the formation. For now, we'll define the strong side as the side

with the most WR's:

In this diagram the left side of the diagram has 3 WR's while the

right side only has 1, so we'll designate that side as the strong

side. Because we're running an under front, this means that we'll

place the reduction away from the strong side, or to the single

receiver side. In terms of gap assignments, even though the offense

is in a spread trips formation, the run assignments are no different

from what we saw above when there was a TE. The space between the LT

and Y is still the C-gap, and the DE is still responsible for it.

The space outside of Y is still the D-gap, and the SLB is still

responsible for it. The main other difference is that the SLB lines up off the LOS to put him in better position to cover something like a slant by H, and so that he can see his keys on the OL and in the backfield better.

When the offensive formation doesn't have a clear strong side, we'll

set the reduction to the RB's alignment:

In this diagram there are two WR's on each side of the formation,

meaning that neither side has more WR's. The RB is aligned to the

right of the diagram, so we set the reduction to that side.

Those are some of the ways that we'll set our base front. Above I

mentioned that, although many teams run Under Cover-4, the devil is

in the details. I also mentioned that LB assignments are less

straightforward than I made it sound. Well, those LB assignments are

the kinds of details that I'm talking about, and right off the bat we

can see some differences from what we were running with Buh.

First, how is run defense supposed to work, in more detail? In any

defense, LB's can't just blindly rush into their gap. Let's see why:

This is a spread version of “power” against our base defense.

From the diagram it looks like the RG is pulling through the hole to

block the MLB, but in reality thinking of him as blocking the MLB

doesn't fully describe the problem.

What this play is really doing is removing a gap from the right side

of the formation and inserting it into the left side of the

formation. On the right side of the formation before the snap there

is an A-gap outside the center, a B-gap outside the RG, and a C-gap

outside the RT. When the RG leaves, however, there is just one big

gap between the center and RT where there used to be two gaps (one

between the center and the RG, and another between the RG and the

RT). Meanwhile, pre-snap on the left side of the formation there was

an A-gap outside the center, a B-gap outside the LG, and a C-gap

outside the LT. When the pulling RG inserts himself between the LT

and LG, he splits the B-gap into two separate gaps (one outside of

him, one inside of him). If the WLB just blindly rushes downhill at

the snap, the defense won't have the numbers that it needs to stop

the play:

Whichever side of the pulling RG the MLB attacks (I've drawn him

attacking the outside shoulder of the RG here), the RB can cut to the

other side and gain yards. In order to stop this play, the WLB has

to recognize that the RG is pulling and follow him across the

formation:

Put into the terms we've been using, the pulling RG takes a gap away

from the right side of the formation and re-inserts it on the left

side of the formation. If the defense is going to stay gap sound,

they also have to take a defender away from the right side of the

formation and insert them to the left. The MLB can then attack the

outside shoulder of the pulling RG while the WLB attacks his inside

shoulder. The defense stays gap sound.

So the LB's (and to some extent the DL) can't just rush their gaps,

they have to read the offense's blocks and react in the correct way

to counter them. The details of Kaufman's specific brand of Under

Cover-4 are all about how they're taught to react to different kinds

of plays. Let's see how the run fits worked against just one of UA's

favorite plays and formational tendencies.

Here's a classic UA/UO-style play. Early in the game UA wanted

to run inside zone toward the reduction and away from trips:

The actual playcall here is to hand the ball off to the RB. All of

the other bells and whistles attached to this play are just ways to

protect that running play by punishing the defense for overselling to

stop the RB run.

For

the inside zone part of the play, the OL is zone stepping to the

right. The RT will block the DE, the RG will block the DT, and the C

will release to LB level. The LG will take the other DT, and the LT

will release to the MLB.

The

key block here is the RG vs. his DT. This block is the RB's first

read, and he cuts off of it. He has a number of choices depending

on what happens. He's seeing whether the DT goes inside or outside

of the RG. Say that the DT goes outside the RG and plays hard into

the B-gap:

In this case, the right A-gap should be open. If the WLB tries to

fill that A-gap, the C will have a great angle to block him (as shown

in the diagram above). The RB will cut to the left of the RG and get

downhill. What if the MLB gets over the top of the LT and into that

A-gap?

If the MLB comes over the top, as I've drawn, or if the A-gap is

otherwise filled, then the RB will cut it all the way back and get

yards inside the DE. What if the DE crashes down to take the RB

on that cutback?

This is where the offense wants to start punishing the defense for

selling out to stop the RB run. In this case the QB should keep the

ball, read the SLB, and decide either to keep the ball himself or to

throw the bubble screen to H. As a side note, we can see from this

set of rules that the old-school option defense of hitting the QB on

every play doesn't work against the zone read. If the DE plays the

QB, either by slow-playing him or straight up hitting him, then the

QB will just hand the ball off and there won't be anyone in position

to defend the cutback by the RB:

What's a defense to do? The offense has an answer no matter what

happens! Well, not quite. The defense CAN take it all away, and

here's how we did it against UA:

This all starts with the defense recognizing the RB's alignment and

reading the blocks of the OL. This does not appear to be a stunt

that is called in from the sidelines. Rather, the defense is ready

for the tendency based on the offensive formation and reading the

blocks of the OL. If the OL zone steps to the right, that sets the

chain of events in the diagram above in motion. On the right of the

diagram, the DT and WLB see the OL zone stepping towards them. The

3-tech DT falls inside the block of the RG into the A-gap, where he

bangs into the center and prevents him from getting to LB level. The

RG is still trying to block that DT, so the DT is able to take out

two blockers (C and RG) all on his own. Meanwhile the WLB takes the

B-gap hard. This automatic stunt takes away the front side zone

play, forcing the RB (if he gets the ball in the first place) to cut

back. On the backside, when the DE sees the OL stepping away from

him, he crashes down hard and plays the cutback. Because the DE

crashes down on the RB, however, the QB should keep the ball. That's fine, because we're scraping the MLB

to the outside as the QB player. This is a read that the MLB is

making. When he sees the OL zone stepping away from him, he comes

around outside of the crashing DE. This leaves the bubble

screen as the only option left, but we're assigning the safeties to

any bubble screens. This gives us a 3-on-2 advantage (X and Y

blocking vs. the CB, FS, and SLB):

We wouldn't game-plan the reads like this against every team, but because UA often runs this particular play, we do. Most importantly, although there are a lot of moving parts, the reads are simple: For everyone in the defensive front, they just ask if the OL is zone stepping toward them or away from them, and react accordingly. For the safety, he hardly has to worry about the run at all. He keeps an eye on the receiver that he's already covering, and the second he sees him bubbling for the screen he flies downhill. Easy.

This solution shows a key way in which our defense this year differs

from Buh's, at least as far as I can tell with my limited breakdown

of last year's defense. Buh wanted to involve the safeties against

the run in order to outnumber the offense. Last year Michael Lowe was our leading tackler, Cameron Walker was third, and Avery was all over the place before he got hurt. That's not all because defenses completed a lot of passes against us. This increased responsibility unfortunately also put

the safeties in run-pass conflict. On pass plays they had to drop

back and be deep defenders, while on run plays they had to fly up to

the line of scrimmage. This isn't as crazy as it sounds and is a

reasonably common way to play Cover-4, but we clearly couldn't make

it work. As a result, our safeties easily got caught looking into

the backfield on playaction passes, and we gave up a ton of big

passing plays as a result. Our CB's probably looked worse than they were last year because of these safety assignments.

Kaufman,

even though he's running the same front and coverage, involves the

safeties in the run game much less, at least against these spread

sets. He only asks the safety to line up over his receiver, and to

fly up on him if that receiver runs a screen. In general, Buh wanted

the LB's and DL to spill runs out to the sidelines, where the

safeties could clean up. We often failed to do this, resulting in

those massive outside runs that we saw so much of last year.

Kaufman, on the other hand, puts much more of the onus on the LB's.

He wants to keep all runs inside the OLB's so that the rest of the

defensive front can make the tackle in pursuit, and as a result Jefferson and Barton are our leading tacklers this year. This does ultimately

make us more vulnerable to cut-backs (this is something that I've

seen going back to his Cincinnati defenses), but that's where the

safeties can come up and at least stop the play from going for big

yards. If we start to see big runs up the middle, we might have to

rethink this strategy, but for now it's working.

This element of our UA game plan let us do several things: (1) it let

us defend the run with a 6-man box. If you check out my post on ourown QB run game, you'll see that the defense needs a 7-man box to

have good numbers against 5 OL + 1 RB + 1 QB. Our auto-checks to the

stunts described above messed up UA's run blocking schemes and let us

defend Solomon and Wilson with only 6 men, giving us an extra

defender against the pass and screens. Also, by making our OLB's our

primary run force on the ouside, we've freed up the safeties and

limited some of the plays that killed us last year: Certain types of

screens, QB runs, perimeter runs, and easy deep passes down the middle of the field. As bad as the defense has looked at times this year, we aren't giving up more against runs between the tackles, and we're greatly improved against several of our weak spots from last year.

Art Kaufman

Defense: Coverage

So where do things go wrong? Against UA (and CU), things go wrong

against the pass, and mostly against the quick passing game. Before

getting into coverage, let's talk for a minute about Anu Solomon: A

lot of people are saying that they aren't impressed with him as a QB,

and to an extent I have to agree because of a lack of versatility.

He has three throws that are his bread and butter: The hitch, the

slant, and the fade. He doesn't seem comfortable reading floating

safeties and LB's in the middle of the field, and I don't see him

working many multiple receiver concepts downfield. This doesn't mean

he won't be a good QB, since Goff had a lot of the same problems last

year and has since corrected them, and Solomon and his WR's are way

ahead of where Goff and our WR's were last year on the fade. Right

now, though, he's limited. Fortunately for UA, these throws

complement each other quite well.

Getting back to coverage. We've already looked at some basic coverage shells in another post, so let's talk a little more about

technique, and the different ways that a CB can line up on a WR. The

tightest coverage will come by lining up 1-yard off the WR and

pressing him. If you don't want to do that, you can play off of him

(with the depth depending on the coverage) with either inside or

outside leverage. When you line up inside of the WR, you're

partially conceding routes with an outside release but putting

yourself in position to stop inside releases. Playing with outside

leverage is the opposite. When you're playing with leverage, you'll

want a second defender who can help on the routes that you're

partially conceding. So in Cover-2, the CB will line up with outside

leverage on the WR and will prevent him from taking an outside

release. Meanwhile the safety is inside and over the top. The CB

uses his leverage to force the WR inside to the safety, and the

safety's inside alignment lets the CB play hard against outside

stuff. The CB protects the safety, and the safety protects the CB.

Their respective leverages complement each other:

The problem with UA, in part, was that the fade has an outside

release, while the slant has an inside release:

When you press a WR and he beats you on each of these routes a few

times, you can get caught guessing, and your play against both routes

can deteriorate as the game goes on. If you give up on the press and

play off of this WR with inside or outside leverage, then that impacts the

rest of your coverage. A defense is like a spider web; if you pull on one part of it, every other part of it will change to some degree. If you play with inside leverage to take away

the slant, you need another player deep and outside to help on the

fade:

This, in turn, affects the way that the rest of your deep coverage has to play, and so on. If you play with outside leverage to keep the fade from getting to

the sidelines, you want an inside short player to take away the

slant:

Those pictures look like pretty good options, right? Wrong, because

the offense has two or three other receving threats in the game:

This is Cover-2. Here the CB's are playing outside leverage, and

would hypothetically force the fade inside to the safety near the

hash marks. This puts them in a bad spot against the slants that're

being run, though. The next defenders inside of them are the OLB's,

but they're in a bind. If they cut the slants by the outside WR's

(the dashed lines), they leave a lot of space for the slants by the

inside WR's. If they stay inside the inside WR's (the solid lines),

they leave a big hole for the outside WR's. The MLB can only take

one of the inside WR's slants and really needs to be on the lookout

for a route by the RB anyway, so the defense is in a bad spot here.

What about other kinds of leverage?

Here the defense has rolled coverage to the diagram's left and is

playing Cover-3. The problem here is that you can only roll coverage

to one side of the formation. This might take away double slants to

the left of the diagram, but on the right of the diagram you can't

take both slants, at least if we're assuming that we need to have at

least one LB (MLB) in the box to defend the run.

The simplest solution to these problems, by far, is to have the CB's

press:

The CB's play tight coverage on the slants by the outside WR's, and

the OLB's can sit with inside leverage on the slants by the inside

WR's. It's can also be good against the fade if your CB's are

physical, because they can get a good jam to take speed off the route

and can then force the WR to the sidelines so that there's no space

for the QB to fit the ball into. This is what we would've liked to

do, and if we could've upped our percentage of success against either

the slant or the fade from the press it would've worked.

Unfortunately, our CB's are overmatched against good WR's with size.

It's not just Cayleb Jones. Now against UA and CU, whenever we have

our CB's covering the fade, opposing WR's are almost always more open

than our own WR's are on similar routes, and our WR's are pretty

good. If we had Marc Antony, 2008 Darian Hagan, 2008 Chris Conte before

he moved to safety, or even SQT (just to show it's not all about

size), we beat UA and the CU game is much more convincing. All of

those guys, regardless of measureables, defended the fade much better

than anyone we have right now. More length would also help us break

up some of those slants from a press alignment. More length means

longer arms, making it easier to get a good jam on a tall WR. As it

is, our CB's don't have the combination of size, strength, or

technique that we need. Our best hope of a quick fix is for Darius

White to get things figured out, but the potential of that is all

based on physical stats right now, and those are kind of meaningless

when compared to all of the other factors that make a good football

player. If you can't press, then you're back to playing the leverage

game, with all of the accompanying problems that we saw above.

There

are a number of things we could do to try and disrupt this, but I've

given too much info too fast as it is, so let's try to get a group

discussion going. Obviously we aren't college-level coordinators and

won't solve anything, but discussions like the one I'm about to

propose will help make sense of different coverages much better than

any of my posts can, so let's try this: These are three plays that

caused us repeated problems in the 3rd

and 4th

quarters:

Hitch:

All slants:

Verticals:

You have 11 guys, and you need a call that can defend these three

plays. Preferably, you'll also want your call to limit huge runs

even if you're willing to concede some things in the run game.

Assume Cayleb Jones is the left outside WR (X). Give me your

personnel group of choice, tell me where you want them to line up,

and give me the coverage rules that will let you cover all three

concepts. I'll draw up any suggestions and post them in the

discussion thread, and we'll hopefully get some good conversation going.

No comments:

Post a Comment