You wouldn't know it from my earlier

posts, but defense is my favorite side of the ball. I've focused on

offense so far in part because that's what our coach is supposed to

be known for, but mostly because I don't hate myself enough to break

down last year's defense. Now that I've written some posts on our

offensive positions, formations, and the way that our plays are

supposed to work, I'm going to start incorporating some more info on

defense by looking at interesting things that opposing defenses did

to stop us. The goal of these posts is both to teach defense from

the ground up, and to show the most interesting strategies that were

used against us. This post will look at some basics of a few zone

coverages before moving on to a particular Cover-3 variant used by

Northwestern.

Zone Coverage Primer

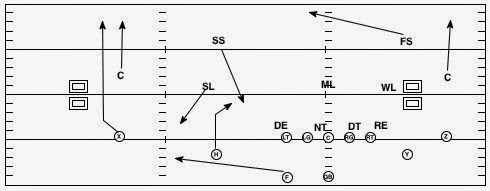

To understand zone coverage, you need to understand how defenses

divide up assignments:

Image taken from glazierclinics.com

There's nothing too tricky here, and a lot of these terms are things

you've probably already heard. To summarize quickly, all defenses

are going to divide the underneath passing zones into five. There's

a hook zone in the middle, curl zones outside of that, and flat zones

outside of those. You can also divide the hook zone in two for

talking about certain coverages, but that's not a major distinction.

For the deep zones, you can have anywhere from two to four defenders

dividing up the field, and they'll usually divide it up

evenly. What makes the various zone coverages different is how you

distribute your back-7 defenders across these zones.

For this post, we'll mostly be interested in underneath coverage.

There are five underneath coverage zones because five is the number

of defenders you need to truly shut down the short stuff. Cover-2 is

the optimal pass defense because it does just this:

To put this in terms of pass zones, there are CB's in the flats,

OLB's in the curl zones, and the MLB in the hook zone. That leaves

you with two safeties to defend the deep stuff, and so they divide

the deep field into halves.

Any

zone coverage with less than five players underneath will require at

least one defender to cover two of those zones. This is especially

the case with quarters (Cover-4):

In this coverage you have four deep

defenders, which only leaves your three LB's to cover the five

underneath zones. This means that your OLB's have to play “curl to

flat.” They'll start out in the curl zones, and widen to the flats

if necessary. This is really a tough assignment against a

well-executed short passing game:

Here the outside receiver is running a

curl and the TE is running a flat route. The SLB is in a bind

because he's responsible for covering two zones. If he runs to the

flat (the solid line in the diagram) then he'll go right past Z, who

will be in a massive void in the curl zone. If he stays under the

curl by Z (the dashed lined in the diagram) then Y will be open in

the flat. Because the SLB is responsible for two underneath zones,

the offense can stretch him by putting a receiver in each of those

zones.

The upshot of all this is that on every

play the offense wants to identify the coverage and, in so doing, the

flat defender on each side of the field. If the coverage forces the

flat defender to be responsible for two zones then they want to

attack him, and there are a number of pass concepts that are designed

to read him. This is one of the most important

concepts in terms of thinking about zone coverages and how to attack

them.

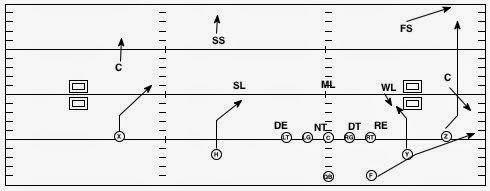

In between Cover-2 (five underneath

defenders) and Cover-4 (three underneath defenders) we have Cover-3.

The standard version looks something like this:

When compared to the Cover-4 diagrammed

above, you can see that the defense has simply dropped one of the

safeties (the SS) into underneath coverage and moved the other safety

(the FS) into the deep middle of the field. This gives the defense

four underneath defenders, and also lets a DB, who is naturally

better in coverage than a LB, help in underneath coverage. We can

see how this will unfold against our curl/flat pattern:

To the left of the diagram this

coverage is just like quarters: The WLB is still a curl to flat

player, and the MLB is still a hook player. On the right of the

diagram, the defense now has two players where they used to have one.

The SS is playing curl to flat, and the SLB is playing hook to curl.

This lets the SS widen with Y while the SLB drops underneath Z (in practice you're still probably going to have a void in the curl zone in between when the SS moves out to the flat and the SLB can get over, but it's going to be tighter). We

can say that the secondary is “rotated” to the right side of the

diagram; while quarters and Cover-2 are balanced coverages with two

DB's on each side of the formation, Cover-3 involves a rotation of

the secondary such that the coverage is stouter on one side of the

field than the other.

There is one more major type of zone

coverage that I should mention, and that's the

self-explanatory quarter-quarter-half coverage (Cover-6, because it's

Cover-2 + Cover-4):

This is just Cover-2 to the right side

of the diagram and Cover-4 to the left. In terms of underneath zones

from right to left, the CB is a flat defender (like he would be in Cover-2), the WLB is a curl

defender, the MLB is a hook defender, and the SLB is a curl-flat

defender. For deep coverage, the FS is playing a deep half, and the

SS and the other CB are playing deep quarters.

This presentation of zone coverages has

been very simplistic, and there are many more things we could talk

about.

One area that I'll get into now is some variations in assignment within these coverages. For now I want to

focus on some variants of Cover-3 that we saw in the Northwestern and

Ohio State games.

If you've looked a little bit at the X's and O's of different coverages, the version of Cover-3 given above

is what you're probably used to seeing. In actuality, it's just one

variant called “Cover-3 Sky.” In this variant, Sky

tells us that a Safety

is the flat defender to the side of the secondary rotation. There's

another variant called Cover-3 Cloud:

This

is still Cover-3 and has most of the advantages discussed above

because of a secondary rotation to the right side of the diagram.

The difference is that the tag Cloud

tells us that the Cornerback

will be responsible for the flat to the side of the secondary

rotation. When compared to Cover-3 Sky, this is just an assignment

switch between the SS and the CB. A major difference is that the CB,

because he's lined up farther outside pre-snap than a SS would be,

has better leverage for playing out-breaking routes. In the diagram above, for

example, you can see that he's in prime position to defend the flat

route by Y. Northwestern used this variant several times, and we'll

return to it below.

Above, I mentioned that the offense

wants to ID the flat defender on each side of the formation and

determine whether or not he's exploitable. Vulnerable defenders will

be guys like the OLB's in Cover-4, or the WLB in Cover-3. The

defense, knowing that this is what offenses like to do, will have

answers to this, and this is where Cover-3 variants can cause

problems. Let's imagine that a team lines up in a Cover-4 shell and

then rotates to Cover-3 Cloud at the snap:

Say that the defense has been playing

some Cover-4, and the OC expects them to do so again. They line up

in a Cover-4 shell. The QB, expecting the CB to bail to a deep

quarter (the dotted line in the diagram) will mistakenly identify the

SLB as the flat defender. For our curl-flat pattern he'll read that

SLB, and will throw to whichever route he doesn't cover. The problem

with this is that the CB isn't bailing to a deep quarter, because

this is Cover-3 Cloud and he's actually the flat defender (the solid line in the diagram).

The QB will see the SLB covering Z on the curl route and will look to

throw to the flat, where the CB will be in perfect position to make

the play.

A disguised Cover-3 cloud can force a

bad throw to the flat, and this was an important part of

Northwestern's strategy in the second half. Ohio State used another

Cover-3 variant called Cover-3 Buzz:

Once again they ran this from a Cover-4

shell. The difference is that the Buzz tag makes the

backer

the flat defender to the side of the secondary rotation (the left in

this diagram). Meanwhile the SS drops into the curl zone, while the

CB's and FS play deep 1/3's on the back end. Why is this variant

effective? When the QB reads the defense, he'll read it as quarters

and ID the SLB as the curl-to-flat defender. Unlike in Cover-3

Cloud, he's actually right here because the SLB is

the flat defender. He'll see the SLB go wide with F, and will look

inside to throw to H in the curl zone. The problem is that this isn't

Cover-4, it's Cover-3 Buzz, so the SS is dropping into perfect

position to make a play.

As

a final note before looking at some specific plays from the

Northwestern game, I should say that Goff doesn't really get confused

by all of this. His first read post-snap is to the safeties, so no

matter who's dropping into underneath zones, if he sees a safety

rotating to the deep middle he knows what's up. More importantly, he

consistently goes to the right place with the ball when he sees this.

Keep this in mind while reading the next section.

Northwestern and Cover-3 Cloud:

With 3:47 left in the game Northwestern was ahead 37-30. Their QB

Trevor Siemian had just thrown an INT to Alex Logan, giving the Bears

the ball on the 50 yard line with plenty of time to tie the game.

Goff dropped back to throw deep to Chris Harper, only to see the ball

intercepted at the 9. For various reasons this looked like a frosh

QB making a rookie mistake, and to an extent that's true. This play

is part of a larger story, however, and really illustrates that every

success or failure on the football field has a history, and is the

end result of a game-long strategic battle between the players and

coaches on each side.

To

fully understand Goff's interception, we have to rewind the tape

about nine minutes to the 12:30 mark in the 4th

quarter. Our offensive playcall is “Stick,” a quick-game concept

that's worked up to this point to the tune of 6/8, 49 yards (BTW, if

you memorize anything from these posts it should be Stick, followed

closely by Power, Y-Cross, and 4-Verticals):

Goff

read this pretty well all night, as the stat line suggests. Three

times Northwestern was in Cover-1 (man coverage with a FS deep), and

he shredded them with the slants to the two receiver side (3/3, 32

yards). He also read some secondary rotations correctly and threw to

the side away from the rotating DB. On another occasion he completed

this concept against a zone blitz. Northwestern had also tried to

defend this with some Cover-6, but Goff correctly threw to X on the

backside slant:

This

was a play that Northwestern needed to stop, and in the 4th

quarter they got into a good call:

The Wildcats disguise the coverage by lining up in a Cover-4 shell

and then rotate to Cover-3 Cloud, with the secondary rotation going

to the field side of the formation. This call means that the CB on

the left of the diagram is free to squeeze the slant by X, because

the SS is rolling to a deep 1/3 behind him in case X goes deep.

Because the CB is playing the flat, the SLB only has to worry about

the curl zone, giving him great leverage to stop the slant by H. To

put this in the terms that we discussed above, the Cover-3 Cloud call

rotates the secondary toward the slants, meaning that none of the

underneath defenders to that side are responsible for two zones.

Cover-3

can only balance out the numbers to one side of the formation,

however, because it only has four underneath defenders. On the other

side we should be golden, because the WLB should be stretched by the

routes of Y and F much like we saw with the curl/flat combination

discussed above. This is where the final wrinkle comes in:

Northwestern has their rush end playing a “peel technique,”

meaning that he rushes the passer unless

the RB releases as a receiver, in which case he drops out of the

rush to cover him in the flat. This means that the WLB doesn't have

to worry about F in the flat, and can instead focus on Y coming into

his curl/hook zone. This peel technique by the end gives

Northwestern a defender in all five underneath zones. Goff sees the

safety rotating to the deep third and correctly looks to the stick by

Y (away from the secondary rotation). He sees that this is covered

and looks to the slants on the back side (all covered) before

throwing up a late ball to Harper (Z). Because the ball's late, the

safety who had been rotating toward the middle of the field has time

to come back over to Harper and break up the pass for a near INT.

Now

we can return to the INT. Remember that above I mentioned how

consistently Goff reads this concept correctly. Also remember that,

at 12:30 in the 4th,

he only threw to Harper as a last resort, after seeing that

everything was covered on both sides of the field. Also remember

that even though the ball was late, the safety had only gotten a

“near” INT.

On

the play with the actual INT, Goff doesn't look at the underneath

routes at all. He looks at Harper all the way and throws to him as

soon as he clears the LB's. I highly doubt that he went rogue for

this one play and made a bad read trying to be a hero, because we

just haven't seen much of that out of him. Instead, I think that

this route was tagged to go to Z all the way if there was a secondary

rotation. Goff looks at the safety, sees him rotating toward the

middle of the field, and tries to hit Harper down the seam. This

isn't, in itself, a bad adjustment. Teams throw seam routes against

Cover-3 all the time at every level of football. The problem is that

we weren't controlling the safety in any way. One way to control him

would be to run a seam at him from the other side of the field:

The

QB could then just read the FS, and throw to the route that he

doesn't take. I haven't seen us vary our quick-game concepts to this

extent, though, so short of calling a different play (probably the best option option if we suspect that we'll see this coverage) the simplest way to control him might ultimately

just be to have Goff move him with his eyes, looking to the slants

while Harper clears the LB's, then gunning a throw down the seam.

Instead Goff never looked anywhere else, letting the safety get the

INT even though the ball was thrown earlier than it was on the previous play. Another option is that if they want to use a DE to

cover a RB, force that DE to cover a RB with something like a

post-wheel combo:

The

nice thing about this switch-up is that it doesn't alter the stick

concept in terms of route distribution, so if the defense actually is

playing quarters you can just make your normal reads. I don't know

to what extent this kind of adjustment is built into our offense,

though, especially in year 1. My hope is that we'll see more of

these minor tweaks as we get more settled in the offense, because

while we have concepts that work well against the most common

variants of each coverage, when the defense makes minor changes we

need to be able to do the same.

Film

Study:

In

the following youtube video I've looped three clips from the TV

broadcast. The first is the near INT at 12:30 in the 4th, the second

is the INT at 3:48, and the third is a full-field replay of the INT.

The first two shots are looped four times each, so to see everything that

I've talked about I'd recommend the following order as the play repeats: Just watch the first loop to see what's going on and note

where the RB lines up. We always run Stick toward the RB's

alignment, so that will be the three receiver side that we see in the

diagrams above. On the second loop, watch that side specifically to

get a sense for the route combination. On the third loop, watch the

receivers on the other side of the formation to get a sense for what

they're doing. On the fourth and final loop of each play, watch the

deep coverage so you can see the safety rotation. The more you do this kind

of thing, the better you'll be able to ID'ing this stuff as you watch

live or on TV. The full-field replay is only looped twice, but

that'll show you the motion of the entire defense and let you pick up

any details that may have been hard to see:

For

any questions or discussion, check out the BI thread here:

No comments:

Post a Comment