One part of understanding an offense is

understanding its tendencies. Some of these might be related to down

and distance (“What do they run on first and ten?”), but many are

also based on formation. It's obvious that you run different plays

out of a 4-wide spread formation than you do out of a three TE power

set. Even in spread offenses that are 4-wide most of the time

formations play a crucial role in understanding an offense's

tendencies and, in turn, in understanding what the offense is trying

to do. This post will break down our offense in terms of the plays

that we run out of our main formations, and the advantages and

disadvantages that each formation has. It'll also look at some of

our “packaged plays,” which are closely linked to the formations

that we run and do some interesting things to our tendencies. It

should be noted that all of my information for this post and those

before it comes from the first three games of the season, and so the

picture might look different by the time we get through

breaking down the rest of the season.

Trips

In the first three games of the season our formations were most

obviously connected to run tendencies. In our offense “trips” is

usually the formation that we use when we want to run “power.”

Let's see why this is:

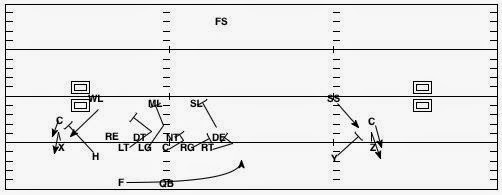

Here we have a doubles formation (two WR's on each side of the field)

with the ball on the left hash. Against this formation, the defense

will almost certainly remove one box defender to the field side of

the formation to match the second WR (Y). In this diagram they've

pulled the SLB out of the box to maintain a 3-on-2 advantage in the

passing game (the FS, SLB, and CB over the Z and Y receivers). To

the boundary side the defense is less worried since there is less

space to cover. Because there is less space to the boundary, there

is less need to pull the WLB out of the box, so they'll do different

things there. They'll either ask him to both fulfill his pass

responsibilities in the boundary side flat and play against the run,

or they'll check to something that relieves his coverage

responsibilities, but the point is that that guy's still a viable run

defender in the box here. Against a doubles formation, therefore,

defenses usually have six defenders in the box (4 DL + 2 LB's). This

gives them a stout run defense because they are matching these

defenders against only five offensive linemen. With that in mind,

let's review the blocking scheme for “power”:

Remember that in our most common version of power the guard away from

the playside will “pull” and block the playside DE. The rest of

the OL will downblock (block away from the playside) and the RB will

(usually) aim to go inside the pulling guard. From doubles, this

play can get into trouble. The LT has to block the RE, the C has to

block the DT, and the RG has to block the NT. The pulling guard will

block the DE, leaving the RT as the only lineman blocking at the LB

level. If anyone's going to block the WLB it has to be H, but that's

a tougher block from this alignment. From the defense's perspective,

the WLB will be keying the LG and the backfield. He'll see the guard

pulling and follow him across the formation, probably unblocked.

Trips has more potential because it evens out the numbers and creates

better blocking angles:

The defense will still move a LB out over the #2 receiver to the

field just as they did against doubles. This leaves six men in the

box. However, in trips we can move the third receiver (Y) in tight

to the OL, to where he's almost playing like a wing TE. Y will block

the MLB. Since the MLB will also be dropping over Y in the pass

game, he'll actually often align closer to Y, making it easier for Y

to block him. The RT will block the WLB, and the rest of the OL

doesn't have to change a thing. All of the sudden, by bringing Y in

tight in a trips formation, we have six run-blockers for six

defenders even though the defense is playing the exact same front and coverage. This process of using our formation to gain a numerical

advantage and better blocking angles is called “front

manipulation,” with the “front” in that label referring to the

defensive front-seven. We know how the defense is going to adjust to

different formations, and so we use a formation that puts them right

where we want them. Notice that bringing Y in tight wouldn't work as

well from a doubles formation:

If we brought Y in tight here, the SLB wouldn't have to leave the

box. This would give the defense seven box defenders against 6

blockers and would still leave the WLB free. This all shows that the

formation that you use is very, very important in determining a

running play's success, even when you're 4-wide most of the time.

Assuming that your blockers can execute (a big assumption in the

first few games of last season), this play should work well against

the basic version of quarters coverage I've drawn it against. It

should work similarly against Cover-2 or a quarter-quarter-half

coverage. If the defense doesn't want to get gashed by power,

they'll have to adjust:

In this diagram the defense has rotated to Cover-3. As a rule,

defenses with one high safety are better against the run than

defenses with two high safeties, regardless of what the CB's are

doing. We can see why this is: because the SS is now aligned over #2

to the field in Cover-3, the SLB doesn't have to leave the box. This

allows the defense to match seven box defenders against six offensive

blockers, once again giving them an advantage. By shifting to

Cover-3, the defense mitigates our front manipulation and puts

themselves in position to stop power.

This would be a problem if power were the only thing we were running

on most of these run plays, but we rarely call a run that doesn't

also have an option to pass. In this way, our offense is near the

forefront in terms of packaging run plays with pass plays. We don't

have as many post-snap options as a Chip Kelly offense, but we have

at least two options most of the time when we run the ball from a

1-back formation. When we're running power to trips, a common play

will look something like this:

When the defense rotates to Cover-3, the CB covering X will be

responsible for a deep outside 1/3 zone. X will sell the downfield

route, push the CB deep, and then run an out underneath him. Our

receivers can get open in this situation every time, and all the QB

has to do is read the secondary rotation. If they rotate a safety

toward the run, he throws. If they do anything else, he hands off.

This packaged play should put pressure on any standard zone coverage.

The defense can start making more nuanced adjustments (or go to man

coverage) to take away the out or confuse the read, but this opens

them up to other things. That's the level of adjustment that'll be

really interesting to get into in later posts, though.

When this play is working as it should, it's absolutely beautiful to

watch. Even better, the defense can't get any adjustments in because

we run it in the hurry-up. Against Ohio State we had a drive where

we ran this on four out of five plays. The results were: Out to

Treggs for 6. Power to Bigelow for 7. Out to Treggs for 4. H-stick

(the only different play so far) to Powe for 9. Power to Muhammad

for 5. We went away from it for the next two plays then, after that,

came out in trips left with Harper as the single receiver on the

right side of the formation. Ohio State, getting sick of the play

and clearly recognizing the formational tendency, came out in Cover-1

(press man with a FS deep) and BOOM, jailbreak screen to Harper for a

41 yard TD. If you want to watch this, it's the drive starting at

3:41 in the 1st quarter.

In the first three games we didn't see a lot of different things out

of trips. On plausible run downs we usually ran a power/pass

package. In passing downs we favored all-curls (a play I haven't

really talked about). The run game did have a few more things going

on to take advantage of defenses that aligned to the trips receivers

without regard for the RB's alignment. Our power/pass packages were

run out of “trips far” formations, where the RB lined up away

from the three receiver side and ran towards them. This is what's

going on in all the diagrams above. We also used a “trips near”

formation with the RB aligned to the trips side. From this we could

run “counter” to the trips receivers:

This is blocked exactly like power and has all the same advantages,

but shows the defense different backfield action. We could also

complement this nicely with outside zone away from the trips side,

taking advantage of defenses that played too hard to the three

receiver side:

So for ID'ing tendencies it's not just about how the receivers align,

but also how the back aligns with respect to them.

Doubles

Because of the WR alignments in trips, there are large parts of our

offense that we don't often run out of it. Doubles is our preferred

formation for basically any passing play, from screens to the quick

game to the downfield passing game. In the run game, because power

is a worse option from doubles we tend toward outside zone plays in

this formation. We still have a numbers deficit in the box, but we

can take care of this in other ways:

This play has three legitimate options when it's called. We can

either throw a quick screen to X, a quick screen to Z, or hand the

ball off to F. We determine which to go with by identifying what's

called the “best located flat defender.” When the QB reads the

defense pre-snap, he first needs to identify whether the coverage is

man or zone. If it's zone, he needs to identify the defender that is

responsible for the flat (the short outside zone) on each side of the

field. In the diagram above I've drawn the coverage as quarters, so

the CB's are playing off and the WLB and the SLB are the flat

defenders. The “best located flat defender” is going to be

whichever of those guys lines up closest to the box. In the diagram

above, the WLB is closest to the box, so he's the best located flat

defender. When we ID a guy like that, we're going to throw the

screen to his side. Because the best located flat defender isn't

widening with the WR's alignment, we have 2 WR's (X and H) against 1

CB, meaning that the quick screen to that side has good numbers.

Because defenses will usually walk a defender out to the field side

of the formation to cover a 2nd WR threat out there, the

best located flat defender will usually be to the short side, and if

you watch closely you'll notice that that's usually the side we throw

these screens to. It also helps that it's a shorter throw, so the

screen to the boundary is more of a quick hitting play and gives the

defense less time to rally to the ball before it's downfield.

If the defense walks out both of those OLB's, then there is no best

located flat defender, and we have awesome numbers in the box for the

run:

The same basic idea says that we should hand it off against man

coverage:

Because Cover-1, which I've drawn here, drops a safety into

underneath coverage, the defense is able to keep six guys in the box,

but that's OK when we're running zone. If you look at the blocking

schemes in all these diagrams, you can see that because this play

aims for the perimeter and works to move the defense laterally, we'll usually

leave anyone from a backside 3-tech and wider unblocked, and that's

not usually a problem. The backside RE, in particular, shouldn't

crash because he's responsible for contain on the QB or on the

reverse. Since we're not blocking him, even though there are six

defenders in the box we still have good numbers, with 5 OL only

needing to block 4 or 5 box defenders. This is a luxury that we

didn't have with power, because power doesn't create lateral movement

to stretch out the defensive front and put distance between the

backside RE and the point of attack.

As one final note on these runs/packaged plays, we can have the WR's

do things other than quick screens if we think it's advantageous. We

often run bubble screens to H and Y, or have the WR's run slants or

outs. These minor adjustments can take advantage of things that

we're seeing from specific defenders or DC's without requiring an

entirely new plan of attack or set of reads.

Because our packaged plays from doubles are pretty versatile and give

us options against a number of defensive looks, we have a strong

tendency to use them on 1st down. In the first three

games of the season we ran the ball or threw a screen on about

two-thirds of our first downs from doubles, with the remaining third

being roughly equally divided between quick game plays and downfield

passing plays. The other down and distance tendencies from doubles

were about what you'd expect. On 2nd and long we mostly

threw, using the quick game and the downfield passing game with

roughly the same frequency. 2nd and medium was 50%

run/screen packages, 25% quick game, 25% downfield passing game,

while second and short tended toward the quick game and screens.

Third and medium or long was almost exclusively a throwing situation.

We didn't often use doubles on third and short, and when we did it

was because we wanted to throw for the first down. If we're running

on third and short then we'll usually go with other formations.

Run Formations

We have a smattering of other formations that we'll use primarily in

run situations. The most common (and most well known) is the bone,

but we actually show some diversity with different formations

according to the gameplan. In this section, since the tendencies

skew heavily toward the run, I'll mostly talk about what we gain and

what we lose when we get out of the spread and into these other

personnel groupings. First, the Bone:

While most think of this as our power running or goal line set, it's

really no heavier than a standard 2-back, 1 TE pro-set. If you

shifted Y to the line of scrimmage and put H in between the QB and F,

that's exactly what you'd have, so this isn't at all equivalent to

the genuine goal line sets you'll see from a pro-style team. It's my

impression that this is part of the reason our offense struggles at

the goal line, but I'll probably go into that more in another post.

Basically, this is a great short yardage formation as long as the

defense is leaving two safeties high to help against the two WR's.

Whereas our spread formations require us to package plays to account

for some of the box defenders, the bone gives us seven blockers for

the seven front defenders, letting us get a hat on a hat. To illustrate

this, we can look at one of the ways that we'll run power from the

bone:

For the OL, the blocking should look pretty familiar by now, and even

remarkably similar to what they're doing in our spread formations.

The difference is that because we have more backs in the backfield,

the defense has more defenders in the box, so the entire play is much

more compressed and the running lanes are smaller, but,

you're able to pull in all the front defenders and

account for them in your blocking scheme. The bone version of power

and spread versions of power accomplish the same thing numerically,

it's just a matter of whether you do it by blocking certain defenders

or by using your formation to remove them from the box. Because we

aren't great at carrying out our blocking assignments, we're better

with the spread versions than we are with this one; every one-on-one

blocking match-up that we set up is a blocking match-up that we have

a good chance of losing, so we're better when we have as few

defenders in the front as possible. Just to round off the diagram

above, you can see that the playside up-back (Y) kicks out the

DE, and the pulling guard and backside up-back (H) both lead through

the hole to block frontside defenders.

The second the defense rotates at least one of those safeties down

into the front, we lose our numerical advantage. The nice thing

about the bone as opposed to a true I-formation is that, while

I-formation teams will usually show a strong tendency to run toward

the TE, in the bone there is no TE on the line, and so we can and

will run all of our plays to either side, and the defense has nothing

tipping them off. If they do rotate a safety down to one side of the

formation, we can run to the other side just as well, and I'd assume

that the QB can change the direction of the run if he sees a safety

rotate down.

Now we've seen one back and three back sets, which leaves the

personnel grouping that most intrigues me: 20 personnel, or two

backs, zero TE's, and 3 WR's:

I'm interested in this formation for a few reasons. First, I've seen

WSU and Texas Tech use various 2-back sets (usually split backs) a

fair amount, so it seems like it'd be easy to integrate with our

concepts. One major advantage of these sets is that they can

diversify the run game. If the defense is playing quarters (although

they're less inclined to against two backs, but more on that below),

then this has all of the same numerical advantages of trips, because

Y is still removing the seventh defender from the box, and we still

have six blockers for six defenders. By having your sixth blocker as

a FB instead of a TE/3rd WR, you also change the blocking

angle of that sixth blocker (H) by allowing him to lead straight

through the hole. As we saw above, in trips the TE has to come in

from the side of the LB. If the LB reads the play fast, it's tougher

to block him from the side than it is to meet him head-on. On zone runs, the FB can also kick out a DE, so that we can

make sure that he's not crashing down the line of scrimmage.

With 2-backs in the game, the FB does do a lot of kick out blocks,

which also makes him a great target in the play-action game:

This is a play that we ran against Portland State for 11 yards. Here

we're using “gap protection,” which we'll often do when we want

passes to look like runs. The OL will slide in one direction, and a

guard will pull to the opposite side to block the backside edge

defender, which makes this look a ton like power/counter. The RB

then inserts into the space that the guard vacated. The pass concept

in the diagram above is just “Corner,” which I've already talked

about in my post on the quick game. It's enhanced out of this

formation, because since the FB kicks out defenders and arcs out to

LB's so often in the run game, his release from the backfield doesn't

necessarily tip off the LB's that this is a pass. On the play from

the PSU game, the SLB rushed into the box preparing to take on a

block, and Gingold ran right past him to catch the pass and get

upfield. This formation integrates well with our quick game

concepts, therefore, and those are really impossible to run out of

the bone.

So, what do we give up when we go to 2-backs? The biggest loss here

is that we can't really run 4-verticals out of it. This is

important. When we're in doubles, because we have the same number of

WR's on each side of the field, it really behooves the defense to

play a balanced coverage such as Cover-4 or Cover-2. When we go to

trips or 2-back, our formation has a very clear passing strength.

There's absolutely nothing stopping the defense from playing Cover-3

against these formations:

Remember: Any coverage with a single high safety is going to be better against the run regardless of what the CB's are doing. Because the formation has a clear passing strength to the right, the

defense can now spin the SS down over the #2 receiver to the strong

side (Y). Now the SLB doesn't have to leave the box, and the defense

can counter our six blockers with seven defenders. The defense can

also do this against trips, but if they do, they're vulnerable

to 4-verticals:

This is a concept we can run when we're using trips, because the TE

is aligned for an easier release on pass plays and is obviously a

better athlete than a FB. When we're in 2-backs, everything that

lets us gain better angles in the run game also makes us unable to

run 4-verts, which is the best big-play response there is if the

defense shifts to Cover-3 to shut down the run. Even so, the old Air

Raid axiom is that “everything works against Cover-3,” and

there're still plenty of passing concepts that we can use out of our

2-back formations. I'd really be interested to see more creativity

invested in our 2-back groupings, because I think it'd get us a lot

in the run game while still preserving most of our options in the

passing game. As always, though, every change you make in personnel

and formation makes you better at some things and worse at others,

which in turn creates tendencies and makes you more predictable. Hopefully this tour of our formations has made it more

clear exactly how these trade-offs work, and what kinds of

considerations are involved in advocating for more of one formation

vs. another.

Miscellanious Observations

This discussion of tendencies gives a good opportunity to talk about

the run/pass tendencies of our offense. The first point is that

packaged plays are going to skew the numbers in favor of the passing

game. You can add a quick pass to any called running play, since the

OL can run block even if you end up throwing a quick out or screen, so long as the ball is out fast. On called passing plays, however, the OL will be pass

blocking, so you're not going to add a run option to those plays.

The prominent role of packaged plays in our offense is automatically

going to reduce the number of times that we hand off, even if we're

calling a lot of “runs.” Ideally, though, these passes are play-action passes that only turn into play action passes if the defense's reaction is favorable, so it's hard to argue that this is a bad deal in terms of balance.

The

other point is that the worse an offense is in general, the more

they're going to pass, and that's not even taking the score of the

game into account. If an offense wants to be balanced then they need

to stay “on schedule” by running mostly successful plays. For

this post, I'll define successful plays in the following way: A 1st

down play is successful if it gets you to 2nd

and 6 or less. A 2nd

down play is successful if it gets you to 3rd

and 3 or less. I've chosen these cut-off points because if you have

a lot of unsuccessful plays by this metric you're putting yourself in

situations that don't favor running the ball.

Our

offense was skewed toward the run on 1st

and 10. It was also balanced on 2nd

and 6 or less. The problem with our run-pass ratio wasn't that we

wanted to pass too much, but that many of our 1st

and 2nd

down plays weren't successful. Against Northwestern, 25 of our 43

first down plays were unsuccesful, and 18 of our second down plays

were unsuccesful. This means that almost half of our offensive plays

in that game put us in situations that favored the pass. In fact, if

you assume that we passed after every unsuccessful first and second

down (43 plays) and that we were perfectly balanced otherwise (51

plays), you'd guess that we threw ~68 passes. Our actual number of

passes in that game was 65. If we get better at running our offense,

you'll see us in more neutral situations and the run-pass ratio will

balance out.

For questions and further discussion, check out this thread on BI: http://bearinsider.com/forums/showthread.php?p=842321349#post842321349

No comments:

Post a Comment